import xarray as xr # The basic package to deal with data arrays

import matplotlib as plt

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

from mpl_toolkits.mplot3d import Axes3D # For the orbit 3D plottingDiscover EOPF Zarr - Sentinel-1 GRD

Introduction

In this section, we will discover how to search and access Sentienl-1 GRD data through EOPF Zarr samples services and how the SAR data is structured inside the groups and subgroups of a .zarr product.

What we will learn

- 🗂️ How a Sentinel-1 GRD

.zarrproduct is structered? - 🔎 How to visualize some of the variables inside the

.zarrproduct? - 🚀 The practical meaning of some of these Sentinel-1 GRD variables

Prerequisites

This tutorial uses a re-processed sample dataset from the EOPF Sentinel Zarr Samples Service STAC API.

We will be using the Sentinel-1 GRD collection is available for direct access here.

The selected .zarr product from this collection is an item that corresponds to the 08th of May 2017, that visualises the Italian southern area:

S1A_IW_GRDH_1SDV_20170508T164830_20170508T164855_016493_01B54C_8604.

Since this notebook depends on additional packages (beyond the base environment), we will install all the extra dependencies defined in the project’s pyproject.toml. The command below ensures the environment is synchronized with all extras included:

uv sync --all-extras

(run this command on your terminal to get all the extra dependencies)

Import libraries

Helper functions

print_gen_structure

This function helps us to retrieve and visualise the names for each of the stored groups inside a .zarr product. As an output, it will print a general overview of elements inside the zarr.

def print_gen_structure(node, indent=""):

print(f"{indent}{node.name}") #allows us access each node

for child_name, child_node in node.children.items(): #loops inside the selected nodes to extract naming

print_gen_structure(child_node, indent + " ") # prints the name of the selected nodesSentinel-1 GRD structure

Opening the Zarr groups and subgroups

We start by unwrapping Sentinel-1 GRD .zarr products. You can use the xarray functions open_datatree()and open_dataset() to do this.

Let’s keep in mind the following: - set engine = "zarr", specifically designed for the enoding chosen for the EOPF by ESA. - chunks = {}, to keep the original chunking size defined in the .zarrfile metadata

productID = "S1A_IW_GRDH_1SDV_20170508T164830_20170508T164855_016493_01B54C_8604"

url = f"https://objectstore.eodc.eu:2222/e05ab01a9d56408d82ac32d69a5aae2a:sample-data/tutorial_data/cpm_b716/{productID}.zarr"

dt = xr.open_datatree(

url,

engine='zarr',

chunks={}

)

print_gen_structure(dt, indent="") # So we can visualize the data structure easilyNone

S01SIWGRD_20170508T164830_0025_A094_8604_01B54C_VH

conditions

antenna_pattern

attitude

azimuth_fm_rate

coordinate_conversion

doppler_centroid

gcp

orbit

reference_replica

replica

terrain_height

measurements

quality

calibration

noise

noise_range

S01SIWGRD_20170508T164830_0025_A094_8604_01B54C_VV

conditions

antenna_pattern

attitude

azimuth_fm_rate

coordinate_conversion

doppler_centroid

gcp

orbit

reference_replica

replica

terrain_height

measurements

quality

calibration

noise

noise_rangeAs we can see, Sentinel-1 GRD data is organised in a slightly different way compared to Sentinel-2 and Sentinel 3.

There are two main groups with the same subgroups, which correspond to the polarisation information. To identify each polarization you need to check the last two letters of each group.

For example: * S01SIWGRD_20170508T164830_0025_A094_8604_01B54C_VH corresponds to the VH polarization, and * S01SIWGRD_20170508T164830_0025_A094_8604_01B54C_VV corresponds to the VV polarization.

Each polarization group contains the conditions, measurements and quality subgroups. We can list all the groups for the VH polarisation calling .groups.

vh = dt.S01SIWGRD_20170508T164830_0025_A094_8604_01B54C_VH.groups

vh('/S01SIWGRD_20170508T164830_0025_A094_8604_01B54C_VH',

'/S01SIWGRD_20170508T164830_0025_A094_8604_01B54C_VH/conditions',

'/S01SIWGRD_20170508T164830_0025_A094_8604_01B54C_VH/measurements',

'/S01SIWGRD_20170508T164830_0025_A094_8604_01B54C_VH/quality',

'/S01SIWGRD_20170508T164830_0025_A094_8604_01B54C_VH/conditions/antenna_pattern',

'/S01SIWGRD_20170508T164830_0025_A094_8604_01B54C_VH/conditions/attitude',

'/S01SIWGRD_20170508T164830_0025_A094_8604_01B54C_VH/conditions/azimuth_fm_rate',

'/S01SIWGRD_20170508T164830_0025_A094_8604_01B54C_VH/conditions/coordinate_conversion',

'/S01SIWGRD_20170508T164830_0025_A094_8604_01B54C_VH/conditions/doppler_centroid',

'/S01SIWGRD_20170508T164830_0025_A094_8604_01B54C_VH/conditions/gcp',

'/S01SIWGRD_20170508T164830_0025_A094_8604_01B54C_VH/conditions/orbit',

'/S01SIWGRD_20170508T164830_0025_A094_8604_01B54C_VH/conditions/reference_replica',

'/S01SIWGRD_20170508T164830_0025_A094_8604_01B54C_VH/conditions/replica',

'/S01SIWGRD_20170508T164830_0025_A094_8604_01B54C_VH/conditions/terrain_height',

'/S01SIWGRD_20170508T164830_0025_A094_8604_01B54C_VH/quality/calibration',

'/S01SIWGRD_20170508T164830_0025_A094_8604_01B54C_VH/quality/noise',

'/S01SIWGRD_20170508T164830_0025_A094_8604_01B54C_VH/quality/noise_range')Browsing information inside Zarr

Now that we know how to access each polarisation group, we can check where some of the relevant information is stored. These variables will help us visualise results.

For example, to access the measurements subgroup, we can used the .open_dataset() function. Important is to specify the group we are interested in with the help of the group keyword argument.

measurements = xr.open_dataset(

url,

engine="zarr",

group="S01SIWGRD_20170508T164830_0025_A094_8604_01B54C_VH/measurements",

chunks={}

)

measurements<xarray.Dataset> Size: 877MB

Dimensions: (azimuth_time: 16694, ground_range: 26239)

Coordinates:

* azimuth_time (azimuth_time) datetime64[ns] 134kB 2017-05-08T16:48:30.467...

* ground_range (ground_range) float64 210kB 0.0 10.0 ... 2.624e+05 2.624e+05

line (azimuth_time) int64 134kB dask.array<chunksize=(16694,), meta=np.ndarray>

pixel (ground_range) int64 210kB dask.array<chunksize=(26239,), meta=np.ndarray>

Data variables:

grd (azimuth_time, ground_range) uint16 876MB dask.array<chunksize=(2557, 26239), meta=np.ndarray>Antoher way to open a subgroup is converting the information showed on the data tree to a data set information, using .to_dataset() function.

measurements2 = dt["S01SIWGRD_20170508T164830_0025_A094_8604_01B54C_VH/measurements"].to_dataset()

if measurements == measurements2:

print("Yes, it's the same!")

measurements2Yes, it's the same!<xarray.Dataset> Size: 877MB

Dimensions: (azimuth_time: 16694, ground_range: 26239)

Coordinates:

* azimuth_time (azimuth_time) datetime64[ns] 134kB 2017-05-08T16:48:30.467...

* ground_range (ground_range) float64 210kB 0.0 10.0 ... 2.624e+05 2.624e+05

line (azimuth_time) int64 134kB dask.array<chunksize=(16694,), meta=np.ndarray>

pixel (ground_range) int64 210kB dask.array<chunksize=(26239,), meta=np.ndarray>

Data variables:

grd (azimuth_time, ground_range) uint16 876MB dask.array<chunksize=(2557, 26239), meta=np.ndarray>Understanding and visualizing SAR products

We can do the same for other subgroups that contain SAR information.

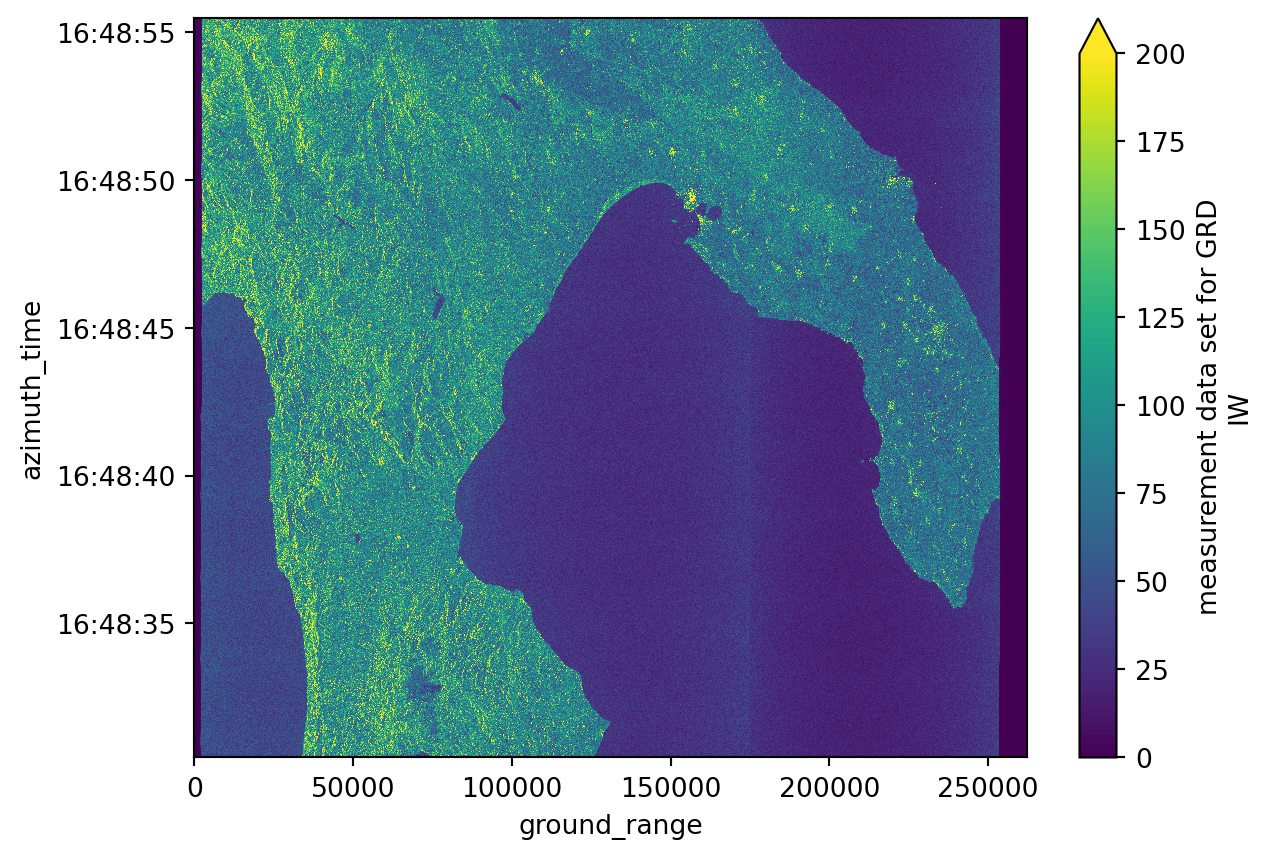

Ground Range Detected

A Ground Range Detected (GRD) product shows us the amplitude of a SAR image. The amplitude reflects the intensity of the radar backscatter, which is the same thing as saying that the amplitude shows how much energy is reflected or absorbed by the surface.

Because the grd variable is very heavy for plotting, we need to decimate it. We will use the dataset created before for measurements to access the grd variable.

grd = measurements.grd

grd_decimated = grd.isel(

azimuth_time=slice(None, None, 10), ground_range=slice(None, None, 10)

)grd_decimated.plot(vmax=200)

plt.show()

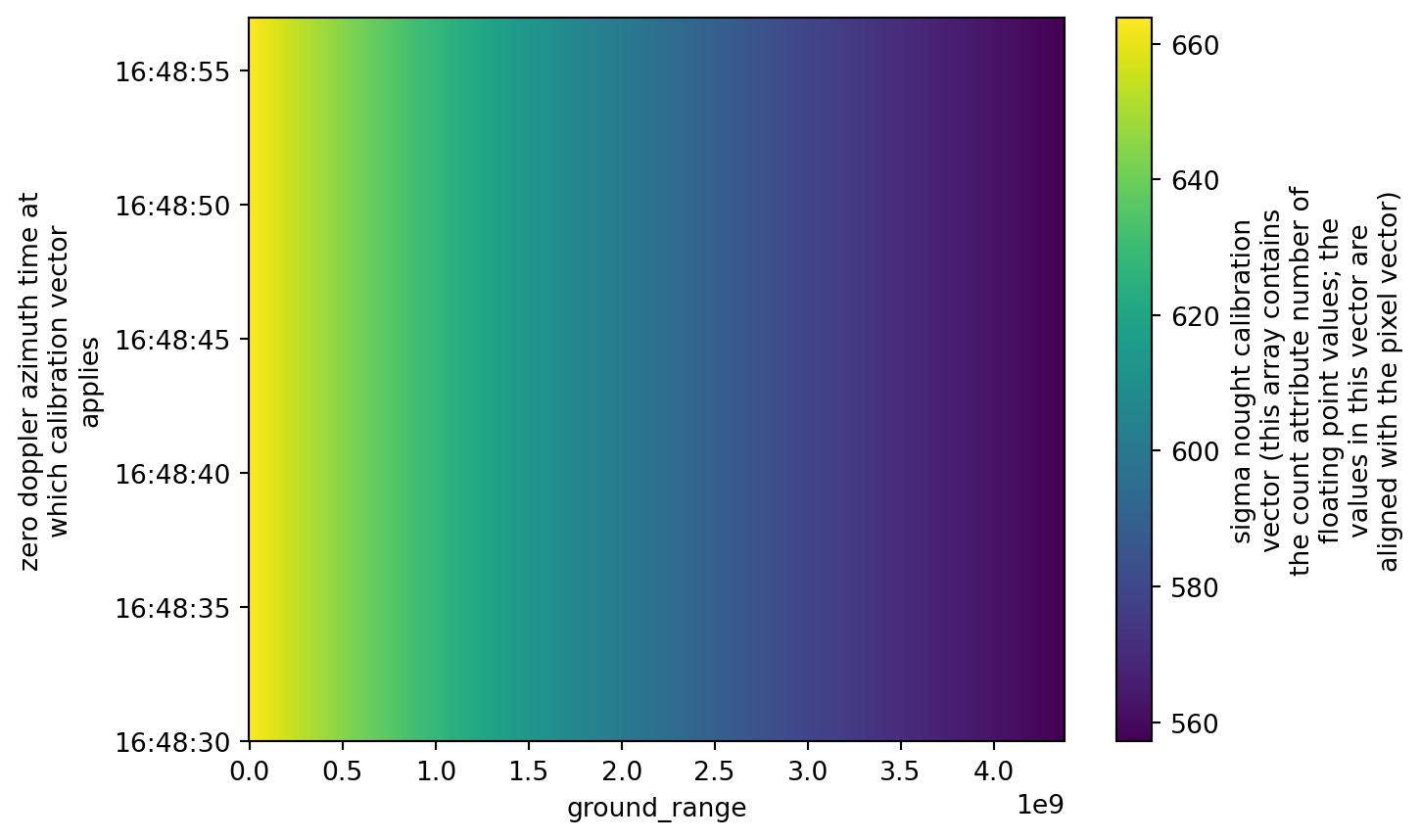

Sigma Nought and Digital Number

We can find the calibration subgroup inside the quality subgroup. It is valuable to take a look at it, as it provides data concerning:

sigma_noughtorbackscatter coefficient: It represents the strength of the radar signal backscattered (or reflected back) from a target on Earth’s surface. See it as how much radar energy is reflected back toward the satellite from a unit area on the ground. This information is rescaled to decibels dB in a common workflow.dn: A digital number representing the raw intensity data measured by the SAR sensor.

calibration = dt["S01SIWGRD_20170508T164830_0025_A094_8604_01B54C_VH/quality/calibration"].to_dataset()

calibration<xarray.Dataset> Size: 292kB

Dimensions: (azimuth_time: 27, ground_range: 657)

Coordinates:

* azimuth_time (azimuth_time) datetime64[ns] 216B 2017-05-08T16:48:30.4679...

* ground_range (ground_range) float64 5kB 0.0 6.677e+06 ... 4.38e+09

line (azimuth_time) uint32 108B dask.array<chunksize=(27,), meta=np.ndarray>

pixel (ground_range) uint32 3kB dask.array<chunksize=(657,), meta=np.ndarray>

Data variables:

beta_nought (azimuth_time, ground_range) float32 71kB dask.array<chunksize=(27, 657), meta=np.ndarray>

dn (azimuth_time, ground_range) float32 71kB dask.array<chunksize=(27, 657), meta=np.ndarray>

gamma (azimuth_time, ground_range) float32 71kB dask.array<chunksize=(27, 657), meta=np.ndarray>

sigma_nought (azimuth_time, ground_range) float32 71kB dask.array<chunksize=(27, 657), meta=np.ndarray>calibration.sigma_nought.plot()

plt.show()

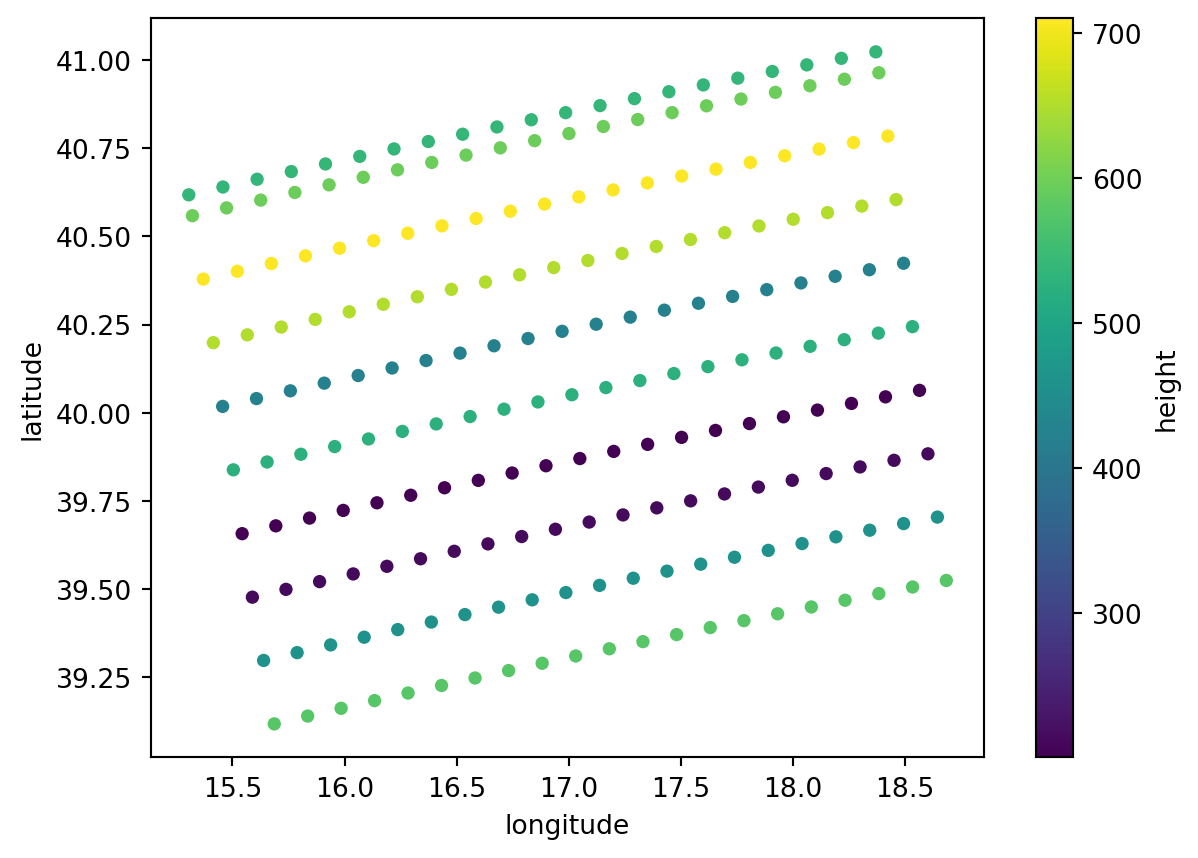

GCP

The gcp subgroup inside conditions is also important. GCP stands for ground control points which are known and precise geolocated references on the Earth’s surface. They can be used later to georeference the GRD image.

gcp = dt["S01SIWGRD_20170508T164830_0025_A094_8604_01B54C_VH/conditions/gcp"].to_dataset()

gcp<xarray.Dataset> Size: 12kB

Dimensions: (azimuth_time: 10, ground_range: 21)

Coordinates:

* azimuth_time (azimuth_time) datetime64[ns] 80B 2017-05-08T16:48:...

* ground_range (ground_range) float64 168B 0.0 ... 2.624e+05

line (azimuth_time) uint32 40B dask.array<chunksize=(10,), meta=np.ndarray>

pixel (ground_range) uint32 84B dask.array<chunksize=(21,), meta=np.ndarray>

Data variables:

azimuth_time_gcp (azimuth_time, ground_range) datetime64[ns] 2kB dask.array<chunksize=(10, 21), meta=np.ndarray>

elevation_angle (azimuth_time, ground_range) float64 2kB dask.array<chunksize=(10, 21), meta=np.ndarray>

height (azimuth_time, ground_range) float64 2kB dask.array<chunksize=(10, 21), meta=np.ndarray>

incidence_angle (azimuth_time, ground_range) float64 2kB dask.array<chunksize=(10, 21), meta=np.ndarray>

latitude (azimuth_time, ground_range) float64 2kB dask.array<chunksize=(10, 21), meta=np.ndarray>

longitude (azimuth_time, ground_range) float64 2kB dask.array<chunksize=(10, 21), meta=np.ndarray>

slant_range_time_gcp (azimuth_time, ground_range) float64 2kB dask.array<chunksize=(10, 21), meta=np.ndarray>gcp.plot.scatter(x="longitude", y="latitude", hue="height")

plt.show()

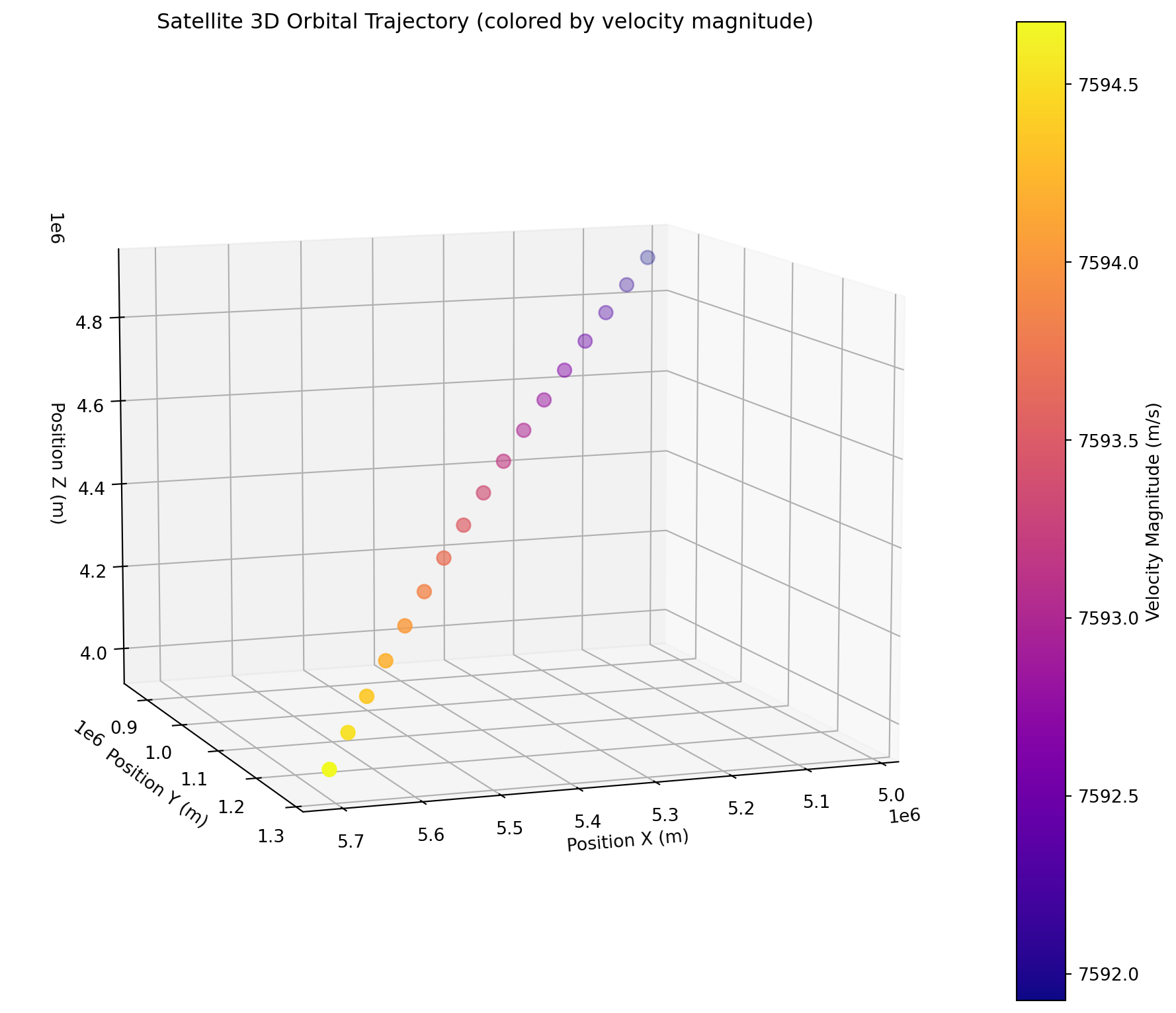

Orbit

orbit subgroup inside conditions is a variable that reflects how the orbital trajectory of the sattelite behaved during the flight.

orbit = dt["S01SIWGRD_20170508T164830_0025_A094_8604_01B54C_VH/conditions/orbit"].to_dataset()

orbit<xarray.Dataset> Size: 952B

Dimensions: (azimuth_time: 17, axis: 3)

Coordinates:

* azimuth_time (azimuth_time) datetime64[ns] 136B 2017-05-08T16:47:24.0541...

Dimensions without coordinates: axis

Data variables:

position (azimuth_time, axis) float64 408B dask.array<chunksize=(17, 3), meta=np.ndarray>

velocity (azimuth_time, axis) float64 408B dask.array<chunksize=(17, 3), meta=np.ndarray># Extract position components (X, Y, Z coordinates in space)

pos_x = orbit.position[:, 0]

pos_y = orbit.position[:, 1]

pos_z = orbit.position[:, 2]

# Extract velocity components and calculate magnitude

vel_x = orbit.velocity[:, 0]

vel_y = orbit.velocity[:, 1]

vel_z = orbit.velocity[:, 2]

velocity_magnitude = np.sqrt(vel_x**2 + vel_y**2 + vel_z**2)

# Convert time to numeric for potential use in point sizing

time_numeric = (orbit.azimuth_time - orbit.azimuth_time[0]) / np.timedelta64(1, 's')

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(12, 10))

ax = fig.add_subplot(111, projection='3d')

# 3D scatter plot: X, Y, Z positions colored by velocity magnitude

scatter = ax.scatter(pos_x, pos_y, pos_z,

c=velocity_magnitude, cmap='plasma', s=60)

ax.set_xlabel('Position X (m)')

ax.set_ylabel('Position Y (m)')

ax.set_zlabel('Position Z (m)')

plt.colorbar(scatter, label='Velocity Magnitude (m/s)')

ax.set_title('Satellite 3D Orbital Trajectory (colored by velocity magnitude)')

# Set a good viewing angle

ax.view_init(elev=10, azim=70)

plt.show()

💪 Now it is your turn

With everything we have learnt so far, you are now able to explore Sentinel-1 GRD items and plot their visuals.

Task 1: Reproduce the workflow with your dataset

Define an area of interest, search and filter the Sentinel-1 GRD collection for the area where you live. Explore the data tree, and the structure of one of the items.

Task 2: Explore other variables

We’ve learnt how to look, explore and plot some specific variables inside the .zarr subgroups, but there are many more. Try to explore and understand what are some other variables, like terrain_height our noise_range.

Task 3: Play with the image plotting

There are many ways to plot an image. Try to play with the variables you are plotting, changing the axis coordinates, maximum values shown or hue values.

Conclusion

This tutorial provided the basics to explore and understand how the Sentinel-1 GRD is structured inside the .zarr format and what to expect to find inside of it.

What’s next?

The next section shows how to perform basic operations on .zarr Sentinel-1 GRD data, using some of the variables we have discovered in this section.